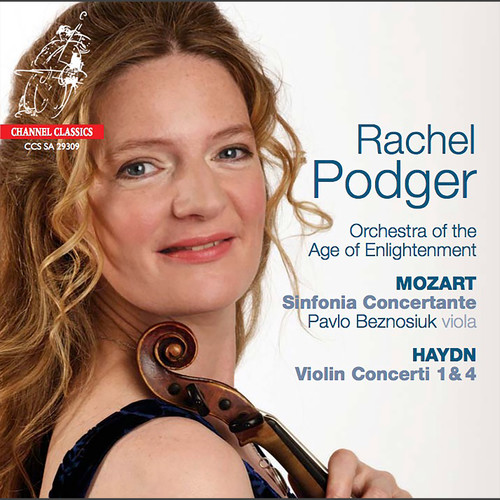

Mozart: Sinfonia concertante - Haydn: Violin Concertos Nos. 1 & 4

第一曲及第三曲所用小提琴为1739年的Pesarinius \r第二曲莫扎特KV364,所用琴分别为1699年的Stradivari小提琴(the 'Crepsi'),以及1720年的Stradivari中提琴('Castelbarco'),皆采用羊肠弦及古典琴弓 \rIt was a joy and an honour to record Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante – such a beautifully\rcrafted masterpiece with those memorable, elegant and distinctive themes in the first\rmovement and both soloists weaving in and out of symphonic textures, the remarkable\rpoignancy of the second movement with its dramatic dialogue which is then dispersed by\rsheer delight and comic playfulness in the Presto.\rDelving into these moods was personally enriching and helped me gain a little bit more\rinsight into Mozart’s genius and being. Pavlo and I had the extreme good fortune to play a\rStrad each! Generously loaned to us by the Royal Academy of Music for this project, we\rsavoured every minute of having these esteemed and valuable instruments in our hands!\r‘Mine’ is a proud instrument which demands careful negotiation and warming before it will\rexpose it’s beautiful colours. An amazing experience in itself to play an instrument like this,\rit was even more of an event when the two Strads met and ‘spoke’ to each other with a\rfeeling of being acquainted, perhaps not for the first time...\rThe two Haydn concertos are of a different era and have a completely different feel.\rComposed around fifteen years earlier at the court in Esterhazy where Haydn lived and\rworked away from the hubbub of musical life, and written for the leader Luigi Tomasini\r(who must have been good at his double stops and arpeggios), they are both charming\rpieces which have brilliance and are a joy to play. Even though written with only string\raccompaniment, there are many colours expressed here; sweet tunes in the high registers\rof the violin with ‘bottomless’ accompaniments and energetic dialogues between rhythmic\rand melodic figures, an ethereal slow movement in the C major Concerto (which I think\revery violinist must play – it gives you an impression of what it might be like to soar in\rheaven...), and bouncy invigorating finales.\rI played my own Pesarinius violin (1739) for these concertos, which I felt suited the\rearlier style of these compositions.\rRachel Podger\r♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢\rIf we imagine Mozart as a performer, we usually \rsee him at the harpsichord or fortepiano, \rand rightly so. Mozart was a gifted keyboard \rplayer, though not a great virtuoso, and indeed \rhe had an aversion to empty virtuosity. But \rfrom childhood, Wolfgang was brought up by \rhis father as a double talent, playing both \rharpsichord and violin, and it was as a violinist \rthat he gained his first appointment. At the \rearly age of thirteen, Mozart became unpaid \rconcertmaster of the court orchestra of the \rArchbishop of Salzburg, where his father \rLeopold was assistant chapelmaster. Even as a \ryoung child, Mozart could hardly bear the shrill \rsound of the violin from nearby, and he \rrequested permission to conduct the court \rorchestra from the harpsichord. To no avail. \rNevertheless, the violin occupied Mozart \rconsiderably in the period 1773-77, and he \roften performed on the instrument himself, \rencouraged, of course, by his father. Leopold \rwas probably also the driving force behind \rWolfgang’s Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major \rfor violin and viola (KV 364). He advised his son \rto master this genre for public concerts; \rorganisers were keen to programme it, since \rthe sinfonia concertante offered audiences the \rattractive spectacle of rivalling soloists. \rIt may well be that Wolfgang performed \rthe Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major with \rhis father in Salzburg. It was there that Mozart \rcompleted the piece in the summer or early \rautumn of 1779. Right from the start there is a \rpeculiarity about the sound of the viola. It is \rtuned a semitone higher than normal, sounding \rmore brilliant and easing the double stopping \rfor the player. Remarkably, the sunny mood \rusually associated with the genre is absent, \rand the Andante in C minor is even rather sad \rand plaintive. This is sometimes believed to \rreflect painful experiences during the composer’s \rjourneys with his mother in 1777-78. In \rMannheim, Munich and Paris he feverishly \rlooked for commissions, but found only negative \rreactions. He fell in love with the beautiful \rsinger Aloysia Weber, the sister of his later wife \rConstanze, but was rejected. In the meantime, \rLeopold pressurised him by letter: “Come on, \rmake sure you get to Paris!”. To make matters \reven worse, Wolfgang’s mother died in Paris. \rIn a most moving letter, Mozart informed his \rfather of her death: “My dearest father…”. This \ris the background to the wonderful Sinfonia \rConcertante in E flat major KV 364 by Mozart. \rMeanwhile, Mozart’s great example, \rJoseph Haydn, was passing his days as court \rchapelmaster to one of the wealthiest noble \rfamilies in Hungary, the Esterházys. The two \rcomposers had not yet met – an event that \rtook place only in 1781 in Vienna – but they \rfollowed one another from a distance, and \racquired each other’s music. \rThanks to the excellent musicians in \rHaydn’s court orchestra, there was no end to \rthe opportunities offered. Several players were \rvirtuosic and ambitious, such as the first \rviolinist Luigi Tomasini and the cellists Joseph \rWeigl and Anton Kraft. Indeed, Haydn composed \rmost of the approximately 45 concertos for \rvarious instruments while he was employed by \rthe Esterházy family, and particularly in the \rperiod 1760-70. \rLuigi Tomasini was one of hundreds of \rItalian musicians who studied in their homeland \rand then travelled across the Alps to become \rorchestral musicians or virtuosi at the many \rcourts of the European nobility. In 1761, \rTomasini was concertmaster of the court \rchapel at Eszterháza, a post directly under the \rchapelmaster, and was therefore in a position \rto write his own violin concertos, which he did \rtwice. His personality and playing inspired \rHaydn, who was apparently greatly impressed \rby Tomasini’s warm tone and brilliant technique, \rto compose specially for him. \rOf the three violin concertos composed by \rHaydn in the 1760s, that in C major was \rcertainly written for Tomasini, and the score \rbears the words “Concerto for violin, written for \rLuigi”. It rather looks as though Haydn went \rout of his way to please his Italian concertmaster \rwith all sorts of musical references to \rhis homeland. The work is still very Baroque. \rThe dotted rhythms (long-short-long-short) \rand long triplet passages (little groups of three \rnotes like a string of beads) seem to have \rcrept in from a concerto by Vivaldi. The middle \rmovement is like a serenade, a sort of Italian \raria without works, with a long-spun melody \rfor the solo violin accompanied by plucked \rstrings – another touch of Vivaldi. In the final \rmovement, Tomasini goes to town in all sorts \rof technical tours de force, such as complicated \rdouble stopping (intervals of a tenth) \rand virtuosic bowing (spiccato). \rAll three violin concertos are scored for \rstrings, and only the concerto in A major has \rtwo oboes and horns added. Haydn may well \rhave written all three for Tomasini, even \rthough this is only mentioned in the C major \rconcerto. Those in C and G are probably the \rearliest, dating from 1761-1765, and that in A \ris the youngest, probably written between \r1765-1770. The three works have in common \rcertain Baroque features, such as frequent \rdotted rhythms and sequences, and the \rtraditional block-like alternation of solo \rpassages and full orchestra. \rClemens Romijn